Makarevich's works are always unexpected. They are unexpected not in their form or content but in the choice of object that they "put to death." One can never predict who the next victim of Makarevich's lethal "Radamanthic" touch will be. We are naturally speaking not about magical manipulations that kill real people but about myths. Makarevich's work is all about destroying myths – public, personal and aesthetic ones. He does not spare himself in the process. A painting made in 1977 depicts a cross next to a grave railing into which the artist's own photograph is inserted. In essence, this theme of self-destruction also lies at the center of his well-known series Changes. One may say that Thanatos – one of the principal heroes of post-modernism – has inspired all of Makarevich's work in the sixties (drawings), seventies and eighties.

One English critic has compared modernism with a grating and post-modernism with a map. What he probably meant, among other things, is that a grating lets one see certain depths and perspectives of the real world, while the painted and delineated surface of the map does not let anything shine through. In other words, the post-modernist deals exclusively with recollections. In a manner of speaking, explorers, seafarers and aviators (modernists) overcame real space and time in order to collect information about the world; scholars and geographers (critics of modernism) drew maps on the basis of this information; and, finally, the maps of an already familiar and described world became part of the post-modernist's artistic consciousness. In this way, the spatial and temporal realities of the world have been "covered over" for a post-modernist by modernist maps, as if by funerary shrouds. A post-modernist can only react to maps, decorating, distorting, adding and completing them. This has given rise to the notion of the "flat" post-modernist consciousness. Indeed, the post-modernist's faith in descriptions may lead him to turn the "map" into a fine net and to shut himself up in a cell or aviary, where he would be prone to give himself over to conclusive and parting sobs, convulsions, doleful meditations, etc.

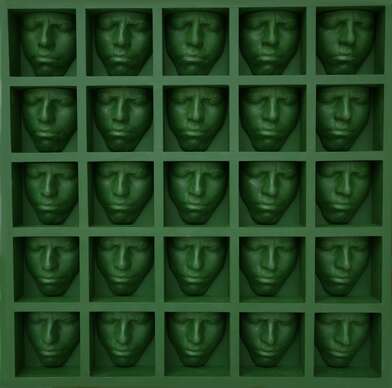

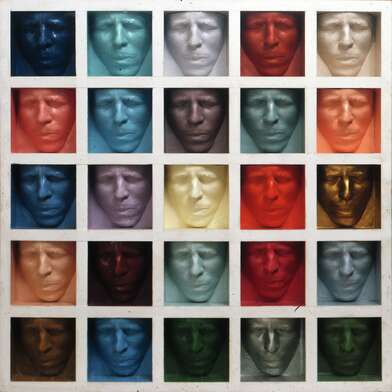

Yet let us return to the Englishman (or German – unfortunately, I have forgotten his name), who compared the two forms of artistic consciousness to the grating and the map. Makarevich outwardly appears to be a post-modernist (the "fatal" perfection of the content level), yet he is a typical modernist on the level of intention and given the "depths" of his discourse. This contradiction can be resolved by taking a look at Russian cemeteries. In contrast to English (or German) ones, Russian cemeteries are a continuous "grating" – in fact, a superposition of gratings. Every tomb is surrounded by a metal railing. These railings overlap and pile up, resulting in boundless "grated" panoramas that constitute enormous modernist fields, which Makarevich sprinkles with his Thanatic "shells" or works. The basic modulus of his art is the box, which also represents the coffin. In the late seventies, he made use of cardboard boxes in 25 Recollections of a Friend (1979) and Dispersion of the Ascending Soul (1979); as the titles suggest, these boxes are also variants of coffins. The subsequent Sensation Cover (one of Makarevich's key works) presents six boxes with different-colored human torsos. Makarevich later made a portrait of Kabakov in a wardrobe. In itself, a wardrobe with the image of a human being placed inside is already a sarcophagus of sorts, yet Makarevich also put a heap of old shoes (a Thanatic motif) in the lower part of the wardrobe and attached a map of the "Chuvash Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic" on the inner side of the wardrobe door. One gets the impression that Kabakov, like Gogol's Chichikov, rides somewhere in this wardrobe or covered cart, seeking to buy "dead souls." Makarevich also depicted Erik Bulatov in a red box (which, incidentally, was clearly meant to resemble a coffin). In these works, Makarevich shows Kabakov and Bulatov in the entirety of their personal myths and with all the principal attributes of their personal artistic worlds; he encases and limits them by coffin walls, i.e., "looks" at them from the point of view of those modernist "grated" cemeteries of the Russian-speaking region which can just as easily destroy the perspective of the personal modernist myth as create a new one. In essence, Makarevich uses this highly favorable topographical and existential standpoint to observe how "gods (modernists) go off into the distance," surrounded by angels (post-modernists); naturally, the latter are usually fallen angels, yet this does not spoil the general picture, whose correlativity always remains intact.

In his painting "Sotheby's," Makarevich cast a Medusan glance at another hero of post-modernism – Pluto. Here he killed or "buried" – and, in the process, introduced into the world of culture and museums – an entire style (called the "Volkov style"), which is very popular and enjoys a lot of financial success. He "crushed" it with a tombstone or ready-made composed of Soviet letters by superposing on the "Volkov" texture the word "СОТБИС" ("SOTHEBY'S") made out of letters that the artist found lying in the street and that came from signs on Soviet banks (the modernism of Soviet finances is still far from being exhausted and represents a very coarse "grating") and by attaching metal handles on both sides of the painting. It is well known that such handles are not found on Soviet coffins, yet they are attached to English and German ones in order to make them easier to carry. In this way, Makarevich gives a precise description (more "existential" than aesthetic) of the stylistic myth of the impetuous contact between Soviet art and Western consumers of cultural valuables that occurred at a famous auction not long ago.

All of Makarevich's artistic actions are ritual acts of burial or a sort of "funeral." The artist's mastery consists in preparing a perfect funerary dress for the "deceased" (the object of the work). The transparency of this conceptual gesture shines through in all his works, although the style of this "dress" changes with the spirit of the times: the "coffins" were rather austere and impersonal in the seventies yet became somewhat brighter and more detailed in the eighties, when the artist began to accord more attention to the objects of the ritual (Kabakov, Bulatov, Volkov) than to its general structure.

Without a doubt, the continuity and conceptual clarity in Makarevich's work also derives from the fact that Makarevich has worked for more than 10 years as a monumental artist, i.e., he has earned his living by working on commissions for institutes, sanatoriums and important public buildings. The combination of a conceptualist and monumental artist is unique. In essence, monumental art in its different manifestations (even the most unexpected ones, such as designing a children's playground) does not break all that much with its original area of activity: decorating cemeteries, sculpting tombstones, and adorning pyramids, mausoleums, and tombs with different types of frescos and reliefs, which typically contain not only heroic depictions of the biography of the deceased but also scenes of a happy future life. In this sense, Makarevich has always been an artist of the future. This would seemingly explain our reaction to slides of his work shown in 1983, which uncovered perspectives that are difficult to grasp even today (in 1988).

FlashArt, 1, 1989