Story of the Wardrobe

A Character Branching Out

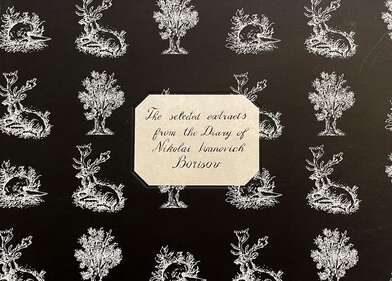

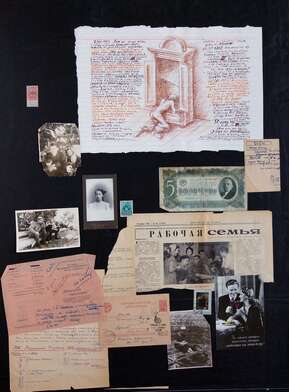

Igor Makarevich’s project Homo Lignum has a longstanding history. It began with the Lignomania exhibition (XL Gallery, 1996), based on the confession of a character who was morbidly obsessed with trees. The “Lignomaniac” appeared in a series of photographsan elderly man dressed in Buratino’s stripy cap and a long-nosed mask, which he appears to have put on to come closer to the state of lignification. Hereafter, Makarevich creates another series of texts and installations, in each of which he re-gathers and re-invents the story of this character. The name and detailed biography of the character appeared in 1998–1999. The artist wrote several texts signed with this name and simulating a personal diary. He presented them to the viewers as Excerpts from the Notes by Nikolai Ivanovich Borisov, or the Secret Life of Trees.

From the pseudo-historical reference preceding the notes, one learns that Borisov was born in Moscow in 1927, worked as an accountant at a woodworking plant, and lived in a communal flat. The main plot of the diaries is a story of insanity or of a mystical epiphany of the character. Nikolai Borisov realizes that he is not like other people; that inside him grows a special tree, which influences his sensory organs, enabling him to feel and understand more, to penetrate the key secrets of the world order. Obsessed with the ultimate desire to turn into a tree, he invents his own system of rituals and prayers. Among the main attributes of his eroticized mysteries is the Pinocchio mask. In a small gallery room, there are catalogues of previous projects by Makarevich, in which the image of a lignified man has been formed. By looking at those catalogues, we can trace the character’s gradual emergence.

Borisov is a miserable man who fails to fit into society, feels scared of the Soviet repressive state, of dogs, the authorities, neighbors, even crows. He flees from this unbearable world into the terrain of his fantasies. He is the “little man” of Gogol’s texts (indeed, the name of the character, Nikolai, is a tribute to the writer) or those of Kafka. In fact, phrases from Kafka’s last diary entry appear in the concluding lines of Borisov’s text. For modernism, the marginal — that which is rejected by the dominant culture, that which does not fit into the frame of “normal” society, that which Bataille calls heterogeneous — becomes the main field of research. Artists, philosophers, and poets aspire to study ultimate, frontier states. “What he bequeathed was not works of art but a singular presence, a poetics, an aesthetics of thought, a theology of culture, and a phenomenology of suffering.” This is the outline of Antonin Artaud’s heritage formulated by Susan Sontag. It could easily be a formula for describing many modernist characters: the artist-creator, possessed by sacred insanity; “a disturbing prophet,” one of the main characters of this epoch. Creating Borisov’s story, Makarevich takes up this image in a grimly humorous fashion, while also researching the modernist mythology of exclusion.

The exhibition Homo Lignum. Story of the Wardrobe at Navicula Artis Gallery is a new extension of the project. Makarevich created a text for it, which did not straightforwardly continue the preceding story but referenced it. The name of the exhibition refers to a text by Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye. Roland Barthes starts his essay about this novel with a reflection on what can be implied by the story of an object. Such a story can be illustrated by listing the names of all people who ever owned the object, or the writer can create a situation in which the object is transformed from one image into another, entering a cycle of transformations through which they pass at a distance from primary existence according to the curve of defined imagination, which transforms the object but does not abandon it. Barthes notes that the narrative of Story of the Eye serves only to enfold a number of such chains of transformations. Jean-Luc Steinmetz, who researched the “work of the words” in the novel, records that one of the key moments in this text is the image of the closet, which turns out to be a device which executes various functions con-nected with the topic of guilt and punishment. Igor Makarevich applies this logic of variation of one object through others, which substitute it. He creates another story, a diary written on behalf of the character who finds a closet in a dump and, being charmed by this object, launches a series of real and phantasmatic transformations. It stops functioning as a piece of furniture and becomes a closet-ward, a closet-urinal, a closet-guillotine, a closet-altar, and a closet-coffin. The guillotine is the “furniture of justice” — the first mechanized device for the execution of death penalty in the history of humankind. In the character’s imagination it simultaneously becomes a device of passion, which delivers sexual pleasure. This image refers to the fantastic mechanisms created by Duchamp, Kafka or Roussel and which the French literary scholar Michel Carrouges amalgamated under the name of “Bachelor Machines.” He accentuated their unified characteristic: mechanizing the erotic, they transform it into the Thanatic.

Similar to other projects in the Homo Lignum series, the artist assembles the exhibition out of photographs, drawings, and diaries of the main character in order to construct a situation in which viewers find themselves inside the fantasy world of the character. Here, one can see drawings with fragments of Story of the Wardrobe and earlier works, which unfold Nikolai Borisov’s story. In the center is the star of the new exhibition, the killing closet-device. The immersion into the shadow world of the character, repulsive and fascinating at the same time, takes a complex route: the text refers to the visual, which refers right back. However, like the bachelor machine — an auto-erotic mechanism — this game is important in its essence: the character becomes the figure through which the reader/viewer gets involved in the entwinement of numerous cultural references, which grow into the character’s story.

Anastasia Kotyleva