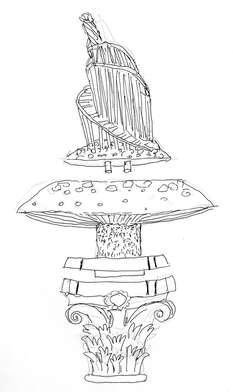

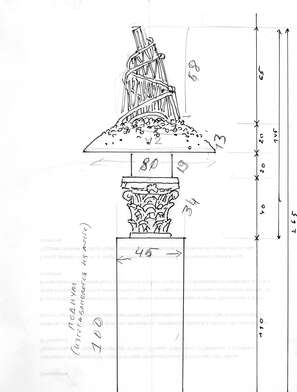

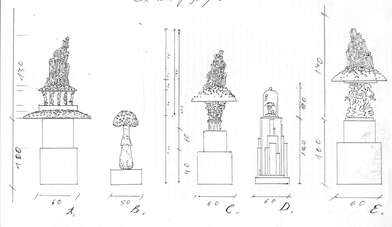

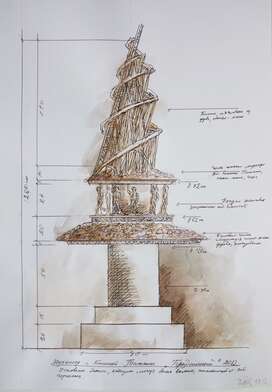

Pagan

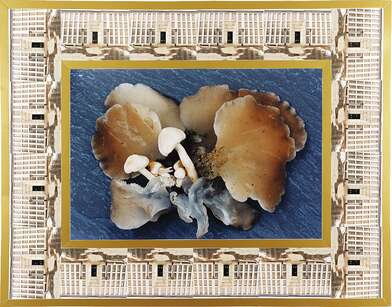

Amanita Muscaria: Looking Back Millenia

Pagan: the first Burmese state in the 11-13th centuries.

Also, a city in Burma on the Irrawaddy river. Buddhist religious centre. Founded in 850.

In the Middle Ages, capital of the state of the same name. Known for its numerous cult constructions, including the Shwezigon Pagoda (11th century).

Soviet Encyclopedic Dictionary

Despite the differences in the linguistic and economic structures of the peoples inhabiting the current territory of Russia, they have one thing in common: since time immemorial, most tribes have used the hallucinogenic amanita muscaria, better known as fly agaric, to achieve altered states of consciousness. With over fifty varieties, this mushroom is to be found on all continents except South America and Australia.

In his monumental two-volume monograph Mushrooms, Russia, and History, the American mycologist R.G. Wasson disputes the claim that the use of fly agaric mushrooms as a drug began around 10,000 years ago. He contends that it actually started much earlier, near the end of the Ice Age, as the fungus shared its habitat with birch and pine trees that covered the Eurasian plains just after the glacial retreat.

The wealth of anthropological evidence provided by Wasson and reviewed in his book clearly confirms the crucial role played by the plant in the lives of the indigenous peoples in this geographical area.

Two anthropologists, Jochelson and Bogoras, members of the North Pacific Expedition organized by the American Museum of Natural History to study the peoples of the coastal areas of Siberia, also wrote about fly agaric and its uses (in 1905 and 1910 respectively). As a rule, the mushrooms were collected in August; only young girls were allowed to pick and dry them. For fear of poisoning, the Koryaks never ate them fresh but dried them in the morning sun. Women were not allowed to swallow any, but they would chew them and keep them in their mouths for lengthy periods.

The alkaloids contained in fly agaric cause poisoning, hallucinations, and addiction. One of the hallu-cinogenic effects is that nearby objects become either very large (macropsia) or very small (micropsia). Episodes of extreme agitation are followed by moments of deep depression. Unlike other hallucinogens, amanita muscaria also leads to physical hyperactivity. It was used for particular sacred, medicinal, and ritual purposes: to communicate with supernatural forces, to predict the future, to find the cause of an ailment, and for pleasure during feasts.

Some tribes, such as the Chukchi, were convinced that mushrooms were “another tribe.” Under the influence, they would always see visions of men — precisely the same number of men as the number of mushrooms eaten. The tundra people believed these creatures would take you by the hand and travel the world with you. They would show the mushroom eater real objects and spirits, following tangled paths and visiting places inhabited by the dead.

An interesting point in the use of mushrooms is the secondary employment of urine. For example, the Koryaks discovered that the hallucinogenic properties of the mushrooms appear in the urine of men who have taken of fly agaric. The man, leaving his dwelling, would relieve himself in a specially prepared wooden container which contained mushrooms. The process was repeated five times until the mushrooms took on the necessary properties. Siberian shepherds may have noticed the link between the properties of mushroom and their presence in urine by observing the behaviour of their reindeer. When the animals ate mushrooms, they developed a craving for shepherds’ urine and would often approach their dwellings to drink it. Every Koryak man carried a sealskin vessel which he used to store his urine. This vessel was a means to lure deer who had gone off to remote pastures. They would return for a taste of urine-soaked snow.

Samoyed forest shamans would eat mushrooms when they were completely ripe and had dried out. It was a dangerous business: if the spirits that inhabited the mushrooms were not well-disposed toward the eater, it was believed that they could kill him. Like the Chukchi, the Samoyeds reported that man-like creatures appeared to them in visions. According to Karjalainen, music was an important element in the Vashugan mushroom ritual. A peculiar ceremony of eating mushrooms existed among the Khanty and Ket peoples, two other Siberian indigenous groups. They would fill the shaman’s tipi-like tent with the smoke of smouldering resinous tree bark; the shaman would eat nothing for a day, then take three to seven caps of fly agaric on an empty stomach before falling asleep. When he woke up, he would narrate what the Spirit had revealed to him through its messengers. The shaman would be greatly agitated, shouting and trembling.

Evidently, a culture associated with the use of amanita muscaria existed everywhere in the southern and western regions of present-day Russia.

The struggle between Christianity and paganism pushed the use of fly agaric further and further north-east. Even so, for thousands of years, the spiritual development of the peoples inhabiting this colossal territory was based on the ecstatic states associated with the consumption of fly agaric. In our view Russia, which has become the arena of all kinds of socio-historical experiments and the Russian character with its immensity and lack of restraint are phenomena connected to a bright-red mushroom, which still grows abundantly in any natural environment marked by the symbiosis of birch and pine.

Much of this essay is based on information from Hallucinogens: Cross-Cultural Perspectives by Marlene Dobkin de Rios.

Igor Makarevich