Life in the Snow

The Tragic End of Life in the Snow

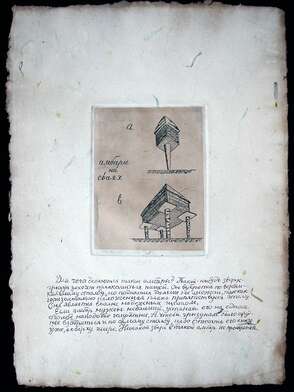

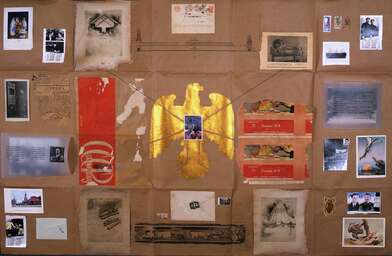

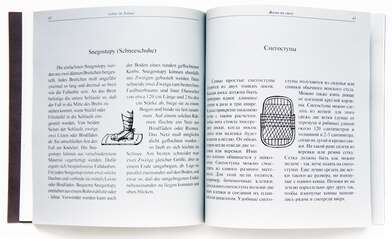

The plot of the exhibition develops in a remarkably clear fashion, much like a classic tragedy. The first room is called The Writer’s Tale. A photograph in a huge wooden frame: the viewer is pierced by the intimidatingly enlightened gaze of an elderly peasant woman, her hand resting on a book. An imposing wooden eagle spreads its wings, the golden key to happiness in its talons. On the shelf, there are logs representing the transformation stages of Buratino, the Soviet Pinocchio: before our eyes, the New Man is triumphantly born. Part two is entitled Life in the Snow. The eagle seems the same but is now made of metal. There he stands, all alone, gradually covered by layer after layer of hoarfrost. Life is freezing away. The golden key has not helped. On the walls, we see twenty ancient-looking engravings depicting snowshoes, primitive sleds, ice houses, and other objects necessary in the glacial cold. The excitement of moving toward the future has cooled.

What all this is about does not need to be explained to post-Soviet viewers. The great era witnessed by them has remained in their memory not only as a set of vivid plastic details but also as a gradually fading motif. To embody it today, you need art that is temporal rather than spatial: the stylization of forms signaling (albeit not encompassing) sots art becomes impossible when forms no longer develop. The genre of visual art that can unfold in time is the installation, the most literary of contemporary arts. This is not a plastic construction of something new but an intellectual reconstruction of what has been, complicated by a multitude of associations. What Makarevich and Elagina are doing here must be called the archeology of culture.

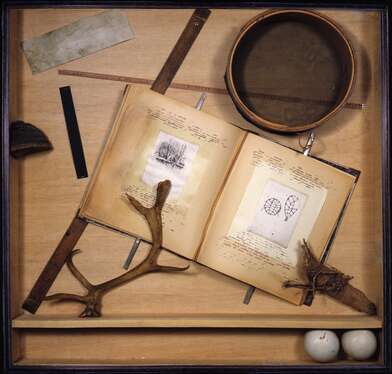

An installation is always a text about a text, and in this case, the concrete source of the whole exhibition is texts found, literally or figuratively, in a garbage dump. One such find is an autobiographical novel by Elena Novikova-Vashentseva, a writer from the “simple people,” who was created by Gorky in the 1930s much like a Kabbalist might create a Golem. “The awakening of genius” began with a blow to the head with a log, sudden like a stroke of lightning, inflicted by her violent husband. “I didn’t feel well afterwards, so they retired me. There I was, all lost and sad, with nothing to do. And suddenly I felt like writing.” The second text is an instruction for Red Army soldiers published in the autumn of 1941: “You can dig a snow cave in a large drift with tightly packed snow. The tunnel leading into the cave should be as long as possible and end at ground level... Winter is dangerous only for those who are not used to it and do not know how to adapt to life in the snow.”

The texts themselves have such a fantastic force of being that there can be no question of competing with their authenticity, let alone of treating it ironically. The line of contemporary artistic consciousness represented not only by Makarevich and Elagina but also by the writer Vladimir Sorokin does not aspire to rational description or analysis. Rather, it seeks to fulfil the task that culture itself seems to assign, a task that can never be completely fulfilled. After all, both the book by the old logtraumatized peasant woman and the instructions to Red Army soldiers on how to properly bury their future remains in the snow belong not to the sphere of professional culture but to that layer between it and reality which in the 20th century produced phenomena so striking and bizarre that post-totalitarian generations might well be envious. Arguably the only comparable art product is the writings of Platonov, whose name immediately comes to mind in the atmosphere of this exhibition.

Makarevich and Elagina are mythological artists. Their installations harbor the heavy spirit of a romantic fairy tale with a bad ending. They describe the world of ideology at the most fundamental level, the level of survival. Here, the locally exotic (primitive sleds and snowshoes) appears as the primordially universal. Wood, snow, fish — these are the urelements in Makarevich’s and Elagina’s universe. The exceptional, the wrong, the strange becomes the most essential. It was the combination of the universal and the marginal, the important and the insignificant that constituted the charm and glory of reflective 1970s art from which Makarevich and Elagina emerged. They were both members of the legendary conceptualist art group Collective Actions. By now, most major representatives of this art form have left Russia, de jure or de facto, and the rest consider themselves retired. But Makarevich and Elagina are still standing guard, waiting for a relief commander with enough historical significance. So far, none is in view. There may be some traces of weariness and decadence in their installations, but it is the decadence of a great era that they are bidding farewell, infinitely and utterly pessimistically.

Еkaterina Degot