Laboratory of Great Acts

Ars Chemica and Contemporary Art

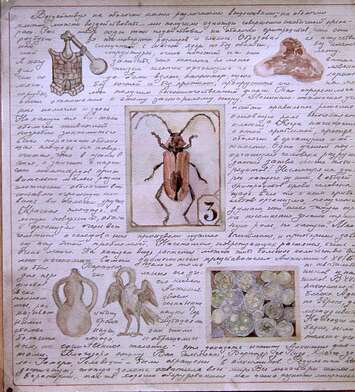

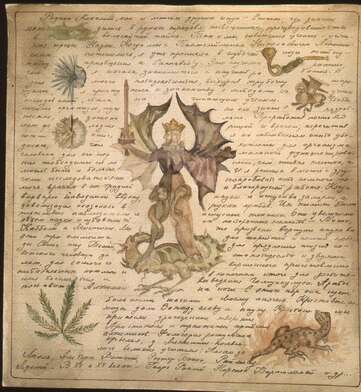

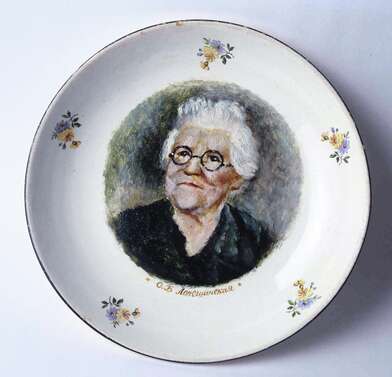

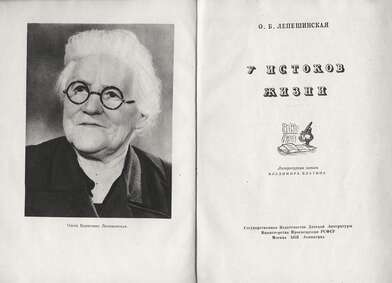

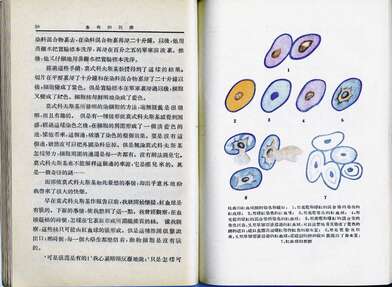

Olga Lepeshinskaya, who for many years headed the Living Matter Department at the Institute of Ex-perimental Biology of the USSR Academy of Medical Sciences, belonged to the poorly researched Order of Marxist Alchemists, whose members (including A. Bogdanov, I. Michurin, and T. Lysenko) had embarked on a quest to create “new forms of living organisms” with revolutionary fearlessness and childlike naivety. As an Old Bolshevik, Lepeshinskaya imagined she could find mysterious “living matter” capable of producing cells and new organisms in an ordinary chicken egg. Her prima materia — that is, the chaotic substance that gives rise to all forms — was always at her fingertips. She would be making some meatballs, and the world’s abysses would open up before her every time that golden liquid — that magical magnesia — poured out of a broken eggshell. The aura of inexplicable fear that has accompanied stories of the Royal Art of Transmutation since times immemorial also surrounds the theoretical constructions of “scientific” alchemists prepared to violate the innermost precepts of human rationality. There is no getting away from scientific magic. Irony might provide some distance, but never enough. Uncannily reminiscent turns of phrase and thought processes keep cropping up all over the place. After all, alchemy itself has not dissolved into chemistry, but has found other forms of existence, for example, in the political theories of the people who carried out the French Revolution.

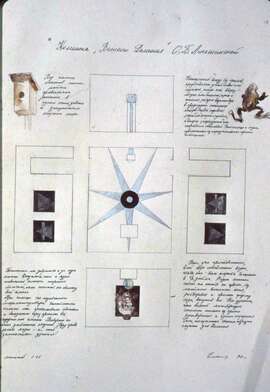

The language and universal symbolism of the Royal Art, woven into the fabric of contemporary culture, can both collapse meaning and create paradoxical spaces. The practice of breaking down borders, which opens the road to the mechanics of transformations, was tried out by the chief alchemist of contemporary art, Marcel Duchamp, in the early twentieth century. Today, it has been supplemented by the discovery of an esthetic alkahest: a universal solvent. With its help, contemporary artists are able to construct spaces which are both absolutely illusionary and absolutely authentic, much like the universe enclosed in a hermetically sealed alchemical retort, where the processes of calcination and distillation, sublimation and fermentation alternate in a chaotic whirl. The elements constituting the matter of contemporary art enable it to condense to the weight of stone and to melt into the blur of writing. The contours of all forms are unstable and fluid. No boundaries exist, for instance, between the lofty delirium of alchemical engravings in ancient manuscripts and faded visual aids that bored many a generation of schoolchildren. There is no opposition between the living and the lifeless, the significant and the insignificant. Everything merges in a symbiosis strangely resembling that very “living matter” from which everything can be moulded, be it history, science, religion, ethics or esthetics.

If an alchemist’s magisterium was unsuccessful, he remained at the dangerous “black” stage known as nigredo. But if he succeeded in advancing, allying with the “secret actor” of alchemical work, he could slip away from the final plunge into mental chaos and the chaos of matter.

An artist who risks working with the prima materia of contemporary culture must be able to clear some space in its turbulent stream for distanced contemplation. Elena Elagina has succeeded in this. She organizes the mental and physical space of her work so as to describe and reveal mental structures that have receded into the depths of consciousness, so as to make visible — in concrete and credible forms — the unconscious mechanics of the chemical theater that is contemporary art. By outlining contours and drawing boundaries, she manages to construct a system of reference points, enabling us to navigate within mannerist chaos in strict compliance with the norms of classical esthetics.

Ekaterina Bobrinskaya