The Writer’s Tale

Letters of Oblivion

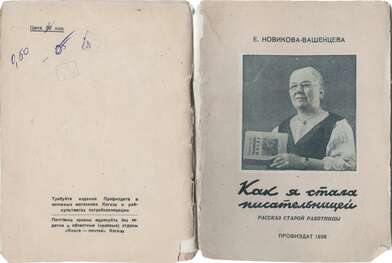

Just like Closed Fish Exhibition and Life in the Snow, the installation The Writer’s Tale was inspired by a marginal publication from the turbulent 1930s: a tiny Profizdat booklet from 1938 entitled How I Became a Writer.

It tells the story of a certain Novikova-Vashentseva, an elderly worker who undergoes a personality change at a ripe old age. In a drunken fit of violence, her husband hits her on the head with a log, and this mutilation transforms the old woman from a battered and unhappy mother of a large family into a vigorous cor-respondent of the proletarian magazine Delegatka (Female Delegate). There is more to come. She goes on to write the autobiographical novel Marinka’s Life, which bears a striking resemblance to Maxim Gorky’s bestseller of the time, Mother. Despite or because of this, the great proletarian writer notices her and blesses her literary career.

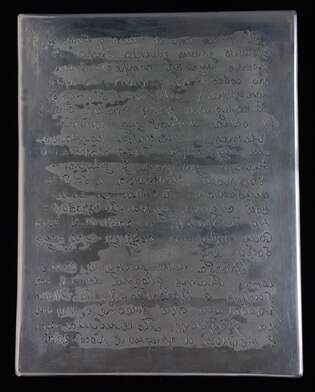

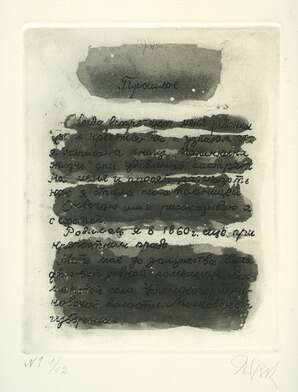

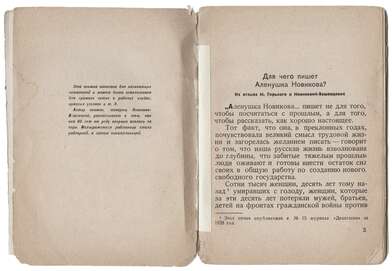

At the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934, Novikova-Vashentseva speaks on behalf of aspiring writers of all nations. I quote the first words of her address to Congress delegates: “I confess, comrades: to my great shame, I cannot speak eloquently and at length. Besides, my memory is poor...” (transcript of the congress, p. 209). An aspiring writer confessing to poor memory: this is the key to the whole story. After all, writing first emerged in order to help forget rather than remember. All ancient peoples kept the art of writing and reading a secret, considered unsafe for the uninitiated. The Russian saying “don’t mend the clothing you’re wearing, or you’ll stitch up your memory” can be interpreted as a fear of putting stitches — runes, letters, lines of writing — onto yourself, thus sealing up the self in a fixed time. Novikova-Vashentseva learns to forget her past, turning her own life into a myth needed by the present. She is fulfilling a state order, for a victorious utopia badly needs a mechanism of oblivion.

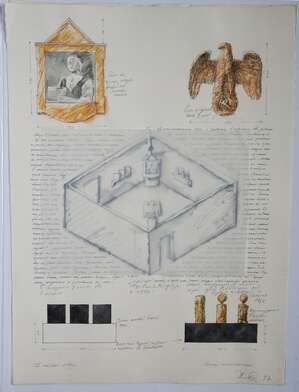

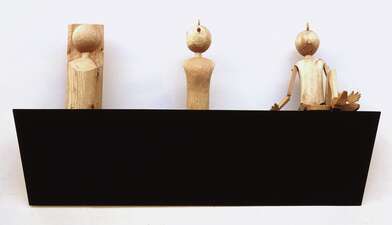

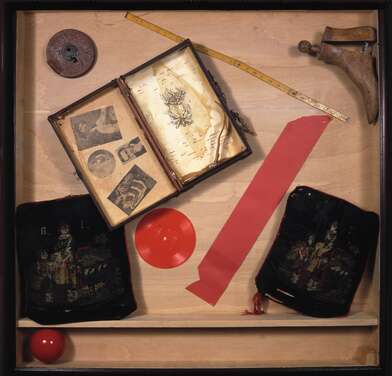

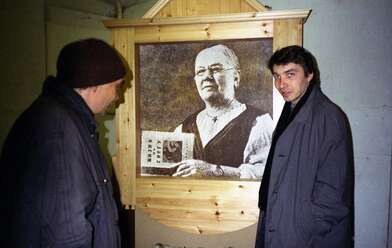

Her simple words are spoken in the sacred language of the present. The world of memory is the realm of the dead. Thus, an old woman whose holy cross is the red five-pronged star, arguably becomes a Bolshevik Mother of God. Accordingly, we have placed her portrait into a massive wooden shrine. The birch log at its base is the magic wand responsible for her transfiguration. By the way, it is from this log that Buratino — the Soviet Pinocchio, an agent of the Great Utopia — is created in our project. Opposite, there is a wooden eagle with a golden key (another symbol from the Buratino story) and picturesque samples of Soviet avant-garde art in its victory over old art history.

The meaning of this installation — which precedes the central one, Life in the Snow — lies in the function of Oblivion when facing the immensity of total Cold.

Igor Makarevich