Closed Fish Exhibition

The Name of the Fish

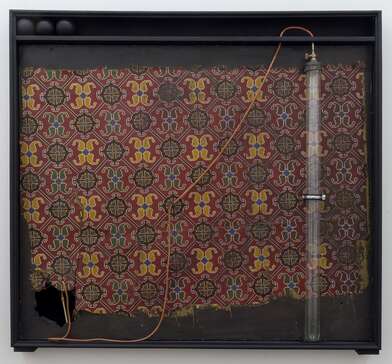

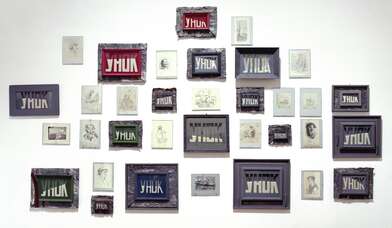

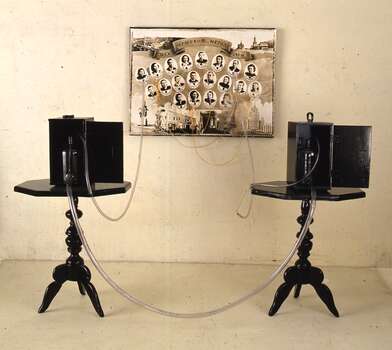

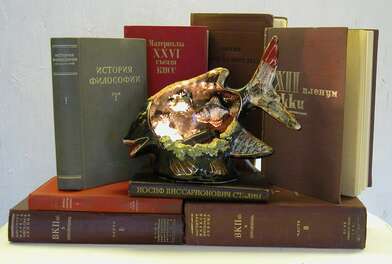

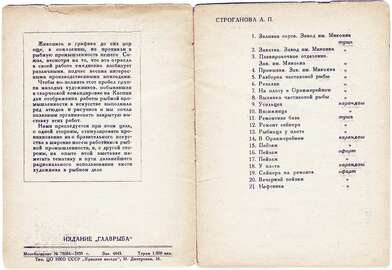

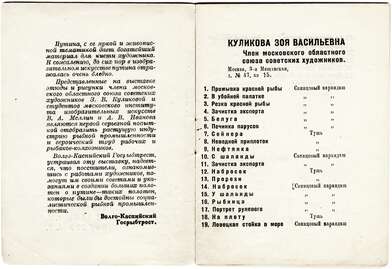

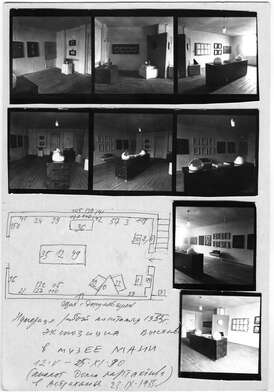

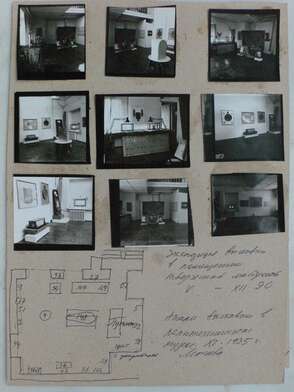

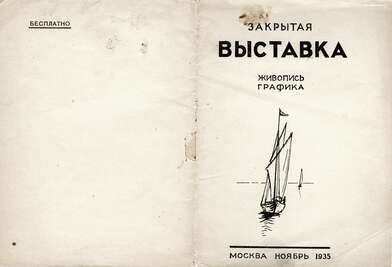

Igor Makarevich and Elena Elagina’s Fish Exhibition is based entirely on coincidences and stratification. The socialist realist exhibition serves as an object of reflection, while the conceptualist exhibition becomes the form of reflection. The exhibited items belong to two spaces simultaneously: the physical space and the textual one. The catalogue of the 1935 exhibition plays the role of a “sky chart” on which all the objects are set out, reckoned, and recorded ahead of time. The labels clearly relate each of the exhibited objects to the catalogue, which acts as a constitution of sorts, giving the entire exhibition the right to exist.

Nevertheless, the peculiarity of the Fish Exhibition lies in the fact that this “structure” must be constantly “turned over.” This enables the material objects to materialize the virtual phantom titles, to bring the un-known works made by unknown artists to life.

“By repeating a lost painting, we give it the status of an existing one,” Kabakov once wrote with regard to his work Tested. Although this idea remains very topical today, Makarevich and Elagina’s gesture is different. It does not submerge into the language of socialist realism but instead “pushes away” (in all the senses of the term), “starts from,” and then “transposes” and “translates.” (All of this recalls certain word games, such as charades employing pantomime and gesture, in which the only permitted means are the creation of a different semiotic series and the equivalent exchange of meaning.) The interest in socialist realist stylistics gives way to an interest in the words denoting it.

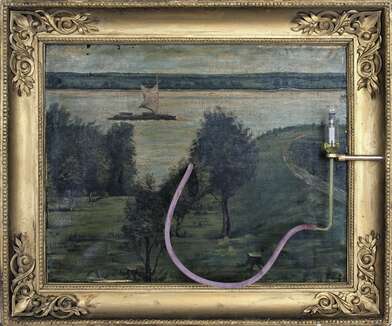

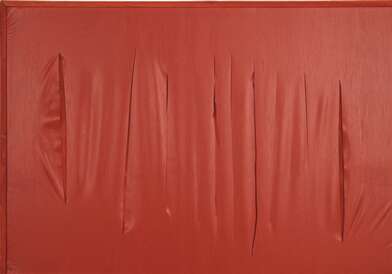

All of the exhibited works are already contained in the 1935 catalogue, with the exception of the composition Fishing Season, which expresses everything that ordinary socialist realists were unable to say. It takes the form of a pathetic utterance in contrast to the individual words (and even syllables) which made up the original Fish Exhibition. In this context, Fishing Season is a large-scale canvas alongside small studies and sketches; from the conceptual point of view, it is an installation surrounded by individual items, and the inner parallel that we are drawing here suggests that classical notions of painting rudimentarily and perhaps unconsciously existed in the Moscow conceptualist school. Fishing Season is a “thematic painting,” the product of the will to unification. At the same time, “oil studies” and “sketches” are not its parts but are literally cast down before it (as is often the case in socialist realism), in the same way as its thematic and painterly aspects are unthinkable without the “elevation” of empirical reality to a mythological level.

The Fish Exhibition reconstructs studies, which are called an “approach to the theme” in socialist realist theory. Contemplation and passive naturalism are permitted in studies. This corresponds well to the artistic act modelled by Makarevich and Elagina, an extremely modest act with exclusively mimetic goals. The “denominative” nature of the exhibition serves to thematize the “denominative” nature of the studies.

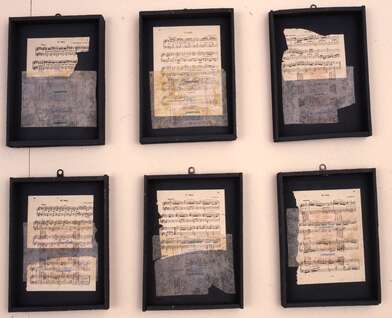

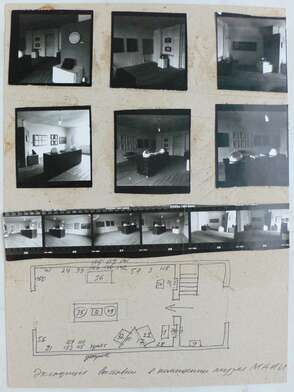

At the same time, it is noteworthy that Kulikova’s, Mellin’s and Ivanova’s studies and sketches are mostly recreated by Elagina and Makarevich as real paintings that hang on the wall in something resembling frames. The “painterly” nature of Makarevich and Elagina’s objects derives from their “fish” theme (the theme of the reproduced exhibition). In a similar way, socialist realist studies had such a large scope only through their relation to the Theme (the study Communist Fishery was undoubtedly perceived as more “painterly” than a study of a non-ideological landscape).

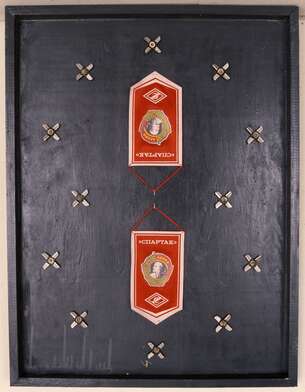

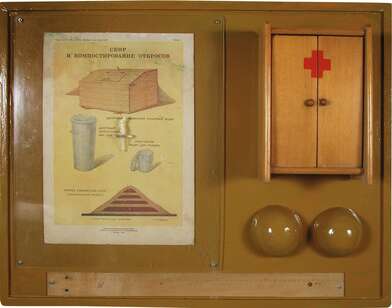

The reflection on the theme “study/painting–word/utterance” that pervades the entire exhibition is so structurally organizing that the Fish Exhibition can be said to be devoted to artistic questions just as much as ideological ones. The myth of Art and its representative Painting also figures here as a typically Soviet myth. In the USSR, art was considered to be not only an ideological activity but also a professional one (somewhat like fish processing). Like the fish industry, it conserved certain archaic rudimentary technologies, such as studies, which were considered to be the “secret of good art,” i.e., they formed the identity of this activity. Decades during which life “had to be somehow lived” witnessed the appearance of an “everyday” layer (the sphere of the “manual” rather than the “mental”) over the ideological foundation: in the words of Boris Groys, “daily life and ideology coincided in an endless text.” All of Kabakov’s work is devoted to the secondary or private mentality that existed within this sphere, derived its vestigial non-reflected ideology from it, and, at the same time, reconstructed Soviet culture from the surrounding monuments of material culture.

Let us now make a few remarks. First of all, the considerable volume of the “manual sphere” that built up over the years created the illusion that purely artistic problems (the problems of craftsmanship and quality) were independent from ideology, a stance that was widespread among broad circles in unofficial art. The Fish Exhibition thematizes this aspect, too, for Makarevich and Elagina label reconstructed objects with their titles and media (e.g., “study, oil”), since such a rigidly formal description of routine media was typical of Soviet art descriptions.

Secondly, although the Fish Exhibition brings out a relatively humane layer of Soviet culture, it is devoted to the theme of fish production rather than consumption. The Soviet ideological system did not consider consumption by itself, but treated it as a form of re-production. This recalls the dichotomy of “contemplation” and “production” that was the driving force of artistic development in the 1920s and 1930s.

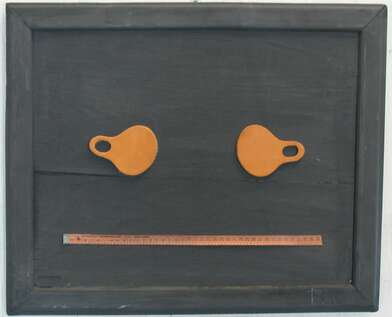

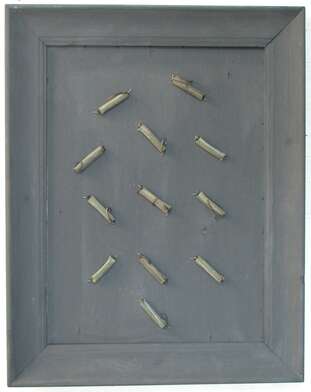

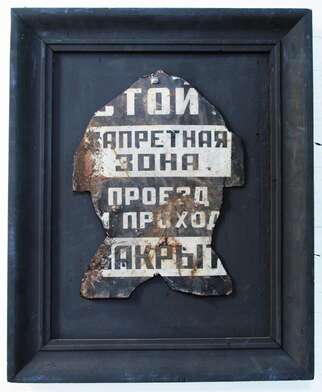

Thus, the Fish Exhibition consummates the unrealized conceptualism of socialist realism. It consummates it by manipulating sheer titles, i.e., the very thing before which art bowed its head and declared itself vanquished in socialist realism. The disintegration into thing and name, whose awareness lay at the root of the conceptualist practices of the 1970s and early 1980s, is palpable and visceral here. Despite the total external literal “adhesion” between each exhibited item and its title, one senses an inner tension be-tween the “other” and the “same” — both an ideal coincidence and an absolute mismatch (e.g., between the toy car and the beer bottle, on the one hand, and the title On the Volga in the Zhiguli Area, on the other; between the radio in a tub of water and the title Take-up Motor at Sea; and so on).

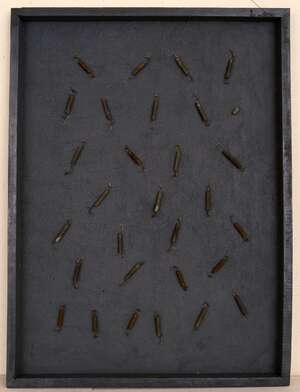

The primitive realistic studies that actually depict exemplary communist fisheries, fish boats, and slit boats are structurally similar to Makarevich and Elagina’s objects: the latter appear to be naively literal (the slit boats have real slits, while the sterns of fish boats are denoted by bags with fish food4), yet their true function is to re-produce something pre-existing and off-limits (the paintings from 1935). In both cases, we are dealing with staged abstractions that appear in the guise of something else, i.e., a mystification. This gives rise to the complex relation between literal and figurative language that constitutes the fabric of the Fish Exhibition.

Makarevich and Elagina reconstitute the “root” meaning of a title in the spirit of naive etymology: common sense serves as a means for removing the spell. Such ostranenie (defamiliarization) is essentially the opposite of the metaphor. Whereas the metaphor (according to Aristotle) is the “transfer of the name,” the name is the only thing that remains in place here, while the missing, substituted works vanish from the logical chain, leaving only their “false likeness” behind.

It turns out that the exclusion of metaphors harbors the risk of figurative speech and that the riddle is greater and more complicated than the answer on the label. The attempts to recreate objects relating to fish using “non-fishy” means (Igor Makarevich told me that anything to do with fish would disturb the general atmosphere) result in the exhibition’s unexpected “poetry,” which derives from subtle shifts and inaccuracies. They create what, in poetics, is sometimes called “semantic assonance” or the emergence of associations; in Makarevich and Elagina’s exhibition, these associations are sometimes verbal (similar names), sometimes purely plastic (similar forms).

This explains why the Fish Exhibition (which may have been an intuitive step) is so topical. By reconstructing socialist realism, it finally leaves it to distant history, so distant that not even its monuments survive. By reconstructing ideology, it returns things to their existence. It puts everything back where it belongs, recreates the fullness of meanings, and makes it possible for something different to exist.

This is why it is crucial that the “closed” Fish Exhibition opens-after all and comes out into the public space.

Ekaterina Degot

__________________________________

Artist Talk of Igor Makarevich and Elena Yelagina at the Closed Fish Exhibition exhibition at Voznesensky Center (in Russian).